Show playing in The Loop connects leaders of The Chicago Outfit to the crime of the century and names the real shooters

It was the crime of the century.

Anyone over the age of 60 remembers exactly where they were on November 22, 1963 when they found out President John F. Kennedy was shot during a parade in Dallas. You remember where you where, how your teachers and parents reacted and the widespread grief citizens of the United States felt. Just like anyone older than 25 remembers September 11, 2001, the date of Kennedy’s assassination is one ingrained in your memory.

But as sure as you are about where you were that day and how you heard, there has been an unprecedented amount of uncertainty behind how the tragic event unfolded.

Yes, the Warren Commission ruled a year later that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone in the murder of the president, firing three shots (in six seconds, with a zig-zagging bullet) from the sixth floor of the Book Depository as the President’s motorcade passed Dealey Plaza. There was no conspiracy, just a lone gunman that took out the most powerful man in the world.

But as the years have passed, that explanation just doesn’t hold up. Recent polls have consistently showed more than 60 percent of Americans do not believe Oswald acted alone, and 77 percent say we will never know how it happened. According to a witness of the actual event, some polls show up to 93 percent of the country believes there was a conspiracy involved.

There have been numerous theories as to who was responsible. Some say it was the CIA, Fidel Castro supporters, the KGB or even then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson who masterminded the crime.

But “Assassination Theater,” a theatrical work based on actual investigative journalism, makes a strong case that it all comes down to the mob. The Chicago Outfit in particular.

Play actors Michael Joseph Mitchell, Mark Ulrich, Ryan Kitley and Martin Yurek enthrall the audience as they portray the big names associated with the mob, the FBI, U.S. government and ‘Overworld’ leaders such as Johnson and Chief Justice Earl Warren, who you’ll find reluctantly accepted the role of leading the investigation and only at the insistence of Johnson. Every bit of the play connects to an actual statement or stance the characters made in real life. There’s no fiction to this, just a really, really good account of what very well may have happened.

Without giving too much away, the show makes a case that it was the mob who organized the hit on JFK and the FBI played a big part in the cover-up. While the Warren Commission claimed Kennedy was shot by only Oswald, who was on the sixth floor of the book depository, this account says there were at least three shooters: one in the Dal-Tex building across the street, another in the Book Depository but on the other side of the building and the third, James Files, from behind the fence in the grassy knoll.

Files, who is still living as a prisoner in Joliet, admits he was the assassin who fired the “kill shot” and specifically detailed the crime to Zack Shelton, a former FBI agent played by Ulrich. Watch the play and you’ll find out just how everything he admitted to checked out when more and more evidence was uncovered.

To this day, anyone can still go to Dealey Plaza and find the angle from the grassy knoll was a straight shot to the spot where the president was hit. Hitting the target from the sixth floor of the Book Depository would be much more difficult.

The story is taken from the perspective of Hillel Levin, an investigative reporter played by Mitchell and Shelton. While Levin was interviewing Shelton in 2007 about a break-in at a reputed Chicago mob leader’s home in the late 1970s, Shelton asked him why he wasn’t doing anything on “the real story.”

“The real story,” aka how the mob killed JFK. They had the motive: the number of indictments against mob leaders had risen 500 percent during the Kennedy years. There’s evidence of Files, and his accomplices, being in Dallas the week of the shooting. And the discrepancies between the president’s first autopsy at Parkland Hospital in Dallas and the one later that day at Bethesda in Maryland have always shown that something fishy was going on.

Find out more about the role of Jack Ruby (the strip club owner who shot Oswald two days later on national television) and how the mob may have also played a role in the death of Robert Kennedy, John’s younger brother and attorney general, while he was running for president five years later by watching for yourself. For Chicago history buffs, you’ll also be intrigued by the mob’s connection to the death of former Mayor Anton Cermak.

‘Assassination Theater’ runs until January 10 at the Museum of Broadcast Communications in The Loop.

You really need to watch this five times to gather all the jam-packed information included in the performance. I consider myself to have above average knowledge of the case, having studied it in both high school and college and having visited the site in Dallas to speak to locals, including witnesses. But even I wish I could have hit the pause button a few times during the show. To allow every bit of information to sink in. Because it’s that juicy. It’s that important.

Eat (and Drink) Your Way Through Sinatra's Chicago

See why the Windy City was without a doubt his kind of town

(Photo by BriYYZ on Flickr)

Frank Sinatra may have been a blue-eyed boy from Hoboken, but he had a real thing for Chicago. Sinatra claimed that he performed in Chicago more than any other city—even Vegas. It was where he made a name for himself as a performer, first working the room as an opening act at the Sherman House Hotel and then finding fame when he took up with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra at the Palmer House.

During the singer’s heyday, he had the run of the streets with his Rat Pack pals and celebrities including Marilyn Monroe and Ella Fitzgerald. Between performances, he spent hours tucked into local clubs. Even his love affairs reflected his love of the city: When Sinatra married Barbara Blakeley, he made sure to have his wedding reception at the Italian Village.

But the crooner of songs like “Chicago” and “My Kind of Town” was also part of the city’s dark side. In 1960, he allegedly helped Chicago mobsters buy votes for the John F. Kennedy campaign. When the mafia came under investigation during JFK’s term, Sinatra paid the price—by playing eight consecutive days of forced performances with the Rat Pack at mob boss Sam Giancana’s night club in the Chicago suburbs.

You can still tour or see a show at many of the performance venues where Sinatra took the stage, but why not toast the singer's 100th birthday on December 12 from one of his favorite watering holes? Each of these bars and restaurants was frequented by Sinatra and his cronies, and together they make up a delicious tour of Frank’s Chicago. If you’re going to raise a toast to Ol' Blue Eyes, consider doing it with a Jack on the rocks. Frank would prefer it that way.

Twin Anchors

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Sinatra and the mob

Just what was Frank Sinatra's association with "made men"?

At some point in the early 1980s, Pablo Escobar built a private zoo. The Colombian drug baron had yet to embark on his campaign of assassinations and bombings that soon terrorised his country, leaving a trail of dead politicians, judges and police in its wake. Business was good. Profits were up. Less than a decade into his career as el Zar de la cocaína, Escobar had cars, planes, sports fields, houses, lakes, farms, all the fine food and drink he could need. An African hippopotamus? Why not? Send one to the ranch – no, make that four. As a local fisherman later said, anything could happen at “the whim of [the] villain”.

Anything, it seems, including an audience with Frank Sinatra. In 1983 Escobar took members of his extended family on a trip to the United States. After queuing for rides at Disney World in Florida and taking a tour of the FBI building in Washington, DC, they embarked on a 760-mile pilgrimage to Graceland, Elvis Presley’s house in Memphis. The wives and children were then sent home and the men went to Las Vegas, gambling their way through $1m of walking-around money and staying at the Caesar’s Palace casino. It was there that the Escobars, masquerading as a group of “important real-estate investors”, were introduced to the headline entertainment.

“We had dinner one night with Sinatra,” recalled Roberto Escobar, Pablo’s brother, who was so thrilled to meet the singer that he “had goose bumps”. “During dinner, Pablo told Sinatra that we were going to make a helicopter tour the next day and Sinatra asked to come with us . . . Frank Sinatra became our guide as we spent about an hour and a half flying all over the area. ‘This is the Colorado River, this is the Grand Canyon.’ He showed us all the scenery.”

Sinatra, it turned out, had been unaware of his new friends’ true identities. A few years later, when Pablo Escobar had become an internationally wanted super-criminal whose cartel was bringing in more than $60m a day (in 1989 Forbes reported that he was worth $3bn), the acquaintance who had introduced them at Caesar’s Palace received a phone call. It was the singer. “I’ve been watching TV,” he said, alarmed and probably pissed off. “Is that Pablo Escobar the guy we met in Las Vegas?”

It was an innocent encounter but one that was in keeping with Sinatra’s lifelong fascination with criminals. He was born in 1915 into a family of Italian-American immigrants who lived in Guinea Town, a cobblestone district of New Jersey populated almost entirely by fellow expatriate countrymen. His parents – Marty, a boxer-turned-fireman, and Dolly, nominally a midwife but also a “facilitator” in the community who carried out illegal abortions and organised for the Democratic Party – owned a boozy tavern during Prohibition. Dolly’s brother Lawrence was rumoured to have been a whiskey hijacker for the bootlegger Dutch Schultz and, it’s said, Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky, Willie Moretti, Frank Costello and Lucky Luciano – a who’s who of the era’s mafiosi – passed through or operated in the neighbourhood. Maybe some of them stopped at Marty’s and Dolly’s bar for a drink.

Frank Sinatra’s involvement with gangsters was a complicated one. The myth, as popularised by Mario Puzo in his novel The Godfather (and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 film adaptation), is that the singer was simply a ring-kissing beneficiary of the Cosa Nostra. In Puzo’s rather dubious fictionalised account, both Sinatra’s contract-breaking departure from Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra in 1942 and his selection for his Oscar-winning acting role in From Here to Eternity (1953) were direct results of a capo dei capi’s interventions.

Yet, although it’s true that the singer associated freely with “made men”, his entanglement with them seems to have been based more on mutual curiosity than a client-padrone relationship. At a time when Italians in the United States were still despised as ethnic outsiders, the lawless, gun-wielding enforcers of Old-World “justice” must have appealed to the young Sinatra, just as, later in his career, his unparalleled status as the world’s best-known Italian American – if not quite the world’s best-known American – must have won him the respect of the uomini di rispetto.

And it seems that he made himself useful to crooks, regardless of whether or not they were Italian. In Sinatra: the Chairman (newly published by Sphere), James Kaplan details the singer’s arrangements with gangsters such as Joseph “Doc” Stacher, a Jewish syndicate leader who allegedly “fronted Frank $54,000” to buy points in the Sands casino in Las Vegas. Sinatra’s relatively clean criminal record and his drawing power as an entertainer made him a perfect fit as a frontman for the business – the gambling town was run more or less openly by mobsters, but appearances had to be kept up.

In 1960, Sinatra and a group of associates applied to buy a majority stake in Cal-Neva, a resort and casino that straddled the border between California and Nevada. This time, the singer, according to Kaplan, was “fronting for Sam Giancana” – the Sicilian-American leader of the Chicago Outfit, the organisation once run by Al Capone. Another co-owner, also behind a protective wall of fronts, was the former diplomat Joseph Kennedy. The first news of the takeover ran in the newspapers on the day that Kennedy’s son John won the Democratic presidential nomination.

Sinatra once said that he had been attending Democratic Party rallies since before he learned to read the slogans on the banners that his mother made him carry, yet his interest in John F Kennedy seems to have been something closer to a crush. During their brief bromance, the singer campaigned vigorously for JFK, whom he nicknamed “Chickie Baby”, and invited him to pal around with the then nascent Rat Pack – his unofficial club that included Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr and the actor Peter Lawford (who was married to Kennedy’s sister Patricia). When Joseph Kennedy summoned Sinatra to ask for his help in getting John the support of the Mob, the singer flew off to meet Giancana on a golf course. Soon after, the gangster “almost certainly” helped engineer voting irregularities in JFK’s favour in the state of Illinois, Kaplan writes.

If, as Norman Mailer once observed, the dream life of America is made up of a “concentration of ecstasy and violence”, Sinatra is surely that dream life personified. His relationship with killers and extortionists, though unfortunate, has become the stuff of myth and his music is curiously shaded by its seedy implications. Dean Martin’s whiskey-soaked yet tonally perfect delivery evokes an unpolluted sense of warmth and congeniality, even when he purrs sinister lines such as: “Brother, you can’t go to jail for what you’re thinking.” (What could he be thinking?) Yet listening to the Voice, as Sinatra was known, is often a deeper, darker experience, especially on his albums of ballads and what he called “saloon” songs. On Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, Sinatra and Strings and No One Cares, the lyrics speak of heartbreak and yearning, but to many 21st-century listeners it is hard to escape the proximity of violence suggested by the singer’s reputation.

It is an undercurrent that, in song, is redirected inwards. We may have heard stories of Sinatra sending an uncomplimentary journalist a tombstone with her name on it, or instructing his driver to go through – not around – the reporters who swarmed him but, in his music, the sense of danger attached to his persona as a star becomes something more abstract. It heightens his performances, making each great song of lost love or longing sound as grand and as important as lost love or longing feels.

There is a desperate seriousness in much of Sinatra’s singing that redeems cliché and shows it to be absolute truth, reminding us that the most profound words we are likely to hear – “I love you” – sound corny and have been uttered billions of times before. “I need your love so badly./I love you, oh, so madly,” he sings in “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You”. Hear a square say this and you may gag. But hear a villain reduced to such depths, a villain who could make anything happen on a whim, and somehow the effect is reversed. There is a strange nobility in the performed debasement of Sinatra, the man who seemed to have it all.

The reality was that he had it all – and nothing at all. Sinatra spent his middle years pining for his errant second wife, Ava Gardner, the screen siren who left him to dally in Spain with one of the toreros who inspired Hemingway’s The Dangerous Summer and whom the obsessed billionaire Howard Hughes jealously had watched by a detective who was later involved in a CIA plot to assassinate Fidel Castro. Success in his various careers placated Sinatra only so long as the sun was up. In the wee small hours, he would stare up at photographs of Gardner, arranged in a shrine in his room, or shoot at them with pellet guns. He couldn’t stand to be alone. “The nights are endless things,” he sings in “When No One Cares”. The lyrics were by Sammy Cahn but in Sinatra’s recording, the singer seems to inhabit every line, every note.

I sometimes wonder what it would be like to listen to Frank Sinatra without any knowledge of his life – would it carry the same weight of lived experience? In the end, any singer’s songs stand or fall on their artistic merits and their emotional resonance with listeners; biography can only have a supplemental relationship with the work. Yet Sinatra was more than a singer: he was a star, and one of the brightest of the 20th century. Who would want to shield himself from that myth and all its violent, ecstatic beauty?

Anything, it seems, including an audience with Frank Sinatra. In 1983 Escobar took members of his extended family on a trip to the United States. After queuing for rides at Disney World in Florida and taking a tour of the FBI building in Washington, DC, they embarked on a 760-mile pilgrimage to Graceland, Elvis Presley’s house in Memphis. The wives and children were then sent home and the men went to Las Vegas, gambling their way through $1m of walking-around money and staying at the Caesar’s Palace casino. It was there that the Escobars, masquerading as a group of “important real-estate investors”, were introduced to the headline entertainment.

“We had dinner one night with Sinatra,” recalled Roberto Escobar, Pablo’s brother, who was so thrilled to meet the singer that he “had goose bumps”. “During dinner, Pablo told Sinatra that we were going to make a helicopter tour the next day and Sinatra asked to come with us . . . Frank Sinatra became our guide as we spent about an hour and a half flying all over the area. ‘This is the Colorado River, this is the Grand Canyon.’ He showed us all the scenery.”

Sinatra, it turned out, had been unaware of his new friends’ true identities. A few years later, when Pablo Escobar had become an internationally wanted super-criminal whose cartel was bringing in more than $60m a day (in 1989 Forbes reported that he was worth $3bn), the acquaintance who had introduced them at Caesar’s Palace received a phone call. It was the singer. “I’ve been watching TV,” he said, alarmed and probably pissed off. “Is that Pablo Escobar the guy we met in Las Vegas?”

It was an innocent encounter but one that was in keeping with Sinatra’s lifelong fascination with criminals. He was born in 1915 into a family of Italian-American immigrants who lived in Guinea Town, a cobblestone district of New Jersey populated almost entirely by fellow expatriate countrymen. His parents – Marty, a boxer-turned-fireman, and Dolly, nominally a midwife but also a “facilitator” in the community who carried out illegal abortions and organised for the Democratic Party – owned a boozy tavern during Prohibition. Dolly’s brother Lawrence was rumoured to have been a whiskey hijacker for the bootlegger Dutch Schultz and, it’s said, Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky, Willie Moretti, Frank Costello and Lucky Luciano – a who’s who of the era’s mafiosi – passed through or operated in the neighbourhood. Maybe some of them stopped at Marty’s and Dolly’s bar for a drink.

Frank Sinatra’s involvement with gangsters was a complicated one. The myth, as popularised by Mario Puzo in his novel The Godfather (and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 film adaptation), is that the singer was simply a ring-kissing beneficiary of the Cosa Nostra. In Puzo’s rather dubious fictionalised account, both Sinatra’s contract-breaking departure from Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra in 1942 and his selection for his Oscar-winning acting role in From Here to Eternity (1953) were direct results of a capo dei capi’s interventions.

Yet, although it’s true that the singer associated freely with “made men”, his entanglement with them seems to have been based more on mutual curiosity than a client-padrone relationship. At a time when Italians in the United States were still despised as ethnic outsiders, the lawless, gun-wielding enforcers of Old-World “justice” must have appealed to the young Sinatra, just as, later in his career, his unparalleled status as the world’s best-known Italian American – if not quite the world’s best-known American – must have won him the respect of the uomini di rispetto.

In 1960, Sinatra and a group of associates applied to buy a majority stake in Cal-Neva, a resort and casino that straddled the border between California and Nevada. This time, the singer, according to Kaplan, was “fronting for Sam Giancana” – the Sicilian-American leader of the Chicago Outfit, the organisation once run by Al Capone. Another co-owner, also behind a protective wall of fronts, was the former diplomat Joseph Kennedy. The first news of the takeover ran in the newspapers on the day that Kennedy’s son John won the Democratic presidential nomination.

Sinatra once said that he had been attending Democratic Party rallies since before he learned to read the slogans on the banners that his mother made him carry, yet his interest in John F Kennedy seems to have been something closer to a crush. During their brief bromance, the singer campaigned vigorously for JFK, whom he nicknamed “Chickie Baby”, and invited him to pal around with the then nascent Rat Pack – his unofficial club that included Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr and the actor Peter Lawford (who was married to Kennedy’s sister Patricia). When Joseph Kennedy summoned Sinatra to ask for his help in getting John the support of the Mob, the singer flew off to meet Giancana on a golf course. Soon after, the gangster “almost certainly” helped engineer voting irregularities in JFK’s favour in the state of Illinois, Kaplan writes.

If, as Norman Mailer once observed, the dream life of America is made up of a “concentration of ecstasy and violence”, Sinatra is surely that dream life personified. His relationship with killers and extortionists, though unfortunate, has become the stuff of myth and his music is curiously shaded by its seedy implications. Dean Martin’s whiskey-soaked yet tonally perfect delivery evokes an unpolluted sense of warmth and congeniality, even when he purrs sinister lines such as: “Brother, you can’t go to jail for what you’re thinking.” (What could he be thinking?) Yet listening to the Voice, as Sinatra was known, is often a deeper, darker experience, especially on his albums of ballads and what he called “saloon” songs. On Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, Sinatra and Strings and No One Cares, the lyrics speak of heartbreak and yearning, but to many 21st-century listeners it is hard to escape the proximity of violence suggested by the singer’s reputation.

It is an undercurrent that, in song, is redirected inwards. We may have heard stories of Sinatra sending an uncomplimentary journalist a tombstone with her name on it, or instructing his driver to go through – not around – the reporters who swarmed him but, in his music, the sense of danger attached to his persona as a star becomes something more abstract. It heightens his performances, making each great song of lost love or longing sound as grand and as important as lost love or longing feels.

There is a desperate seriousness in much of Sinatra’s singing that redeems cliché and shows it to be absolute truth, reminding us that the most profound words we are likely to hear – “I love you” – sound corny and have been uttered billions of times before. “I need your love so badly./I love you, oh, so madly,” he sings in “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You”. Hear a square say this and you may gag. But hear a villain reduced to such depths, a villain who could make anything happen on a whim, and somehow the effect is reversed. There is a strange nobility in the performed debasement of Sinatra, the man who seemed to have it all.

The reality was that he had it all – and nothing at all. Sinatra spent his middle years pining for his errant second wife, Ava Gardner, the screen siren who left him to dally in Spain with one of the toreros who inspired Hemingway’s The Dangerous Summer and whom the obsessed billionaire Howard Hughes jealously had watched by a detective who was later involved in a CIA plot to assassinate Fidel Castro. Success in his various careers placated Sinatra only so long as the sun was up. In the wee small hours, he would stare up at photographs of Gardner, arranged in a shrine in his room, or shoot at them with pellet guns. He couldn’t stand to be alone. “The nights are endless things,” he sings in “When No One Cares”. The lyrics were by Sammy Cahn but in Sinatra’s recording, the singer seems to inhabit every line, every note.

I sometimes wonder what it would be like to listen to Frank Sinatra without any knowledge of his life – would it carry the same weight of lived experience? In the end, any singer’s songs stand or fall on their artistic merits and their emotional resonance with listeners; biography can only have a supplemental relationship with the work. Yet Sinatra was more than a singer: he was a star, and one of the brightest of the 20th century. Who would want to shield himself from that myth and all its violent, ecstatic beauty?

Feds say reputed mobster threatened business partner from prison

Paul Carparelli

Patrick M. O'Connell Chicago Tribune

A judge revoked Outfit-connected businessman Paul Carparelli's bond April 17, 2015, after he allegedly threatened the life of a witness.

"Quit being a FINK and answer my call," convicted mobster writes.

Paul Carparelli, it seems, is not a very gentle guy. He was caught on undercover recordings ordering an associate to "crack" a man who owed a debt. He allegedly sold drugs out of his house, in front of a young son. He managed an extortion ring, federal prosecutors say, and threatened contract beatings to break a victim's legs and knock "the living piss" out of his ex-wife.

And in August, three months after he pleaded guilty in federal court to a trio of extortion counts, he threatened a former business partner from prison, prosecutors allege.

"Doesn't matter if I get 6 months or 6 years when I'm done were [sic] gonna have a talk," Carparelli, a reputed Outfit associate, wrote in an all-capital letters email to the man. "So put your big boy pants on and get ready."

In intercepted emails and prison calls, Carparelli referred to his business partner as a "fink" after he stopped returning his calls and accused him of cooperating with the government, prosecutors said. He also claimed the man owed him money.

"The 1500 means nothing," Carparelli wrote. "Its [sic] the point that matters!!!!!! ... See you when I get out!!!!!! Partner!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"

In the Wednesday filing in federal court detailing the exchange, assistant U.S. attorney Heather K. McShain argued the behavior demonstrates that Carparelli cannot kick his violent tendencies and thus deserves the maximum sentence of 11-plus years in prison.

"This is the life of which Carparelli is 'proud' and to which he is loyal — a lifetime of crime," McShain wrote. Later, she wrote, "Clearly, sitting in prison and awaiting sentencing has done nothing to signal to Carparelli that he must change his ways. ... Only a meaningful sentence will send that message to Carparelli, as well as deter his future criminal conduct and violence.

Carparelli's attorneys disputed many of the government's characterizations of their client, saying in a rebuttal presentence filing that Carparelli often was attempting to collect legitimate business debts and did not use violence or threats.

Carparelli, 47, who allegedly has long-standing ties to the Outfit's Cicero crew, was arrested in July 2013. Agents recovered two guns, $170,500 in cash and nearly $200,000 in jewelry — including a gold bracelet with the name "Paulie" spelled in diamonds — in a safe hidden in the crawl space of his Itasca home, court records show. A 300-pound union bodyguard who was working with Carparelli, George Brown, began secretly cooperating with the FBI.

In a 2013 recorded conversation between the two men, a transcript of which was submitted by McShain in the presentencing court filings, they discussed how to confront a man who owed them money.

Brown: "What exactly do you want this guy to do if this fat (expletive) doesn't have the money?" Brown asks.Carparelli: "OK, if he doesn't have a check today, we need to ring his bell and ask him when are some funds gonna start being available. ..." Carparelli said.

Brown: "Alright, so he's got the go-ahead to (expletive) blast him? That's what you want?"

Carparelli: "Well, I ... I ... I want, I want a response from him first, I want a response from him first, you know what I mean? You understand what I'm sayin'?"

Brown: "Hold on."

Carparelli: "I'd rather just, I'd rather just go there and get a response from him and then, and then if that doesn't work, then we blast him."

In pleading guilty, Carparelli admitted involvement in plots to use intimidation and violence to collect debts on behalf of two businessmen. He was remanded into federal custody for threatening a government cooperator in August. He then wrote a series of emails and made calls to several friends and associates, including attempts to settle debts and finalize the closing of the deli he operated with the man he became upset with in the emails.

"Hey dude at somepoint we need to have a conversation dont know what your problem is but im not gonna be here forever you cant dodge me BUDDY!!!!! so quit being a FINK and answer my call!!!!!!!!" Carparelli wrote to the man on Aug. 7, under the subject header "yo."

Sentencing is scheduled for Dec. 21.

poconnell@tribpub.com

Twitter @pmocwriter

And in August, three months after he pleaded guilty in federal court to a trio of extortion counts, he threatened a former business partner from prison, prosecutors allege.

In intercepted emails and prison calls, Carparelli referred to his business partner as a "fink" after he stopped returning his calls and accused him of cooperating with the government, prosecutors said. He also claimed the man owed him money.

"The 1500 means nothing," Carparelli wrote. "Its [sic] the point that matters!!!!!! ... See you when I get out!!!!!! Partner!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"

In the Wednesday filing in federal court detailing the exchange, assistant U.S. attorney Heather K. McShain argued the behavior demonstrates that Carparelli cannot kick his violent tendencies and thus deserves the maximum sentence of 11-plus years in prison.

"This is the life of which Carparelli is 'proud' and to which he is loyal — a lifetime of crime," McShain wrote. Later, she wrote, "Clearly, sitting in prison and awaiting sentencing has done nothing to signal to Carparelli that he must change his ways. ... Only a meaningful sentence will send that message to Carparelli, as well as deter his future criminal conduct and violence.

Carparelli's attorneys disputed many of the government's characterizations of their client, saying in a rebuttal presentence filing that Carparelli often was attempting to collect legitimate business debts and did not use violence or threats.

Carparelli, 47, who allegedly has long-standing ties to the Outfit's Cicero crew, was arrested in July 2013. Agents recovered two guns, $170,500 in cash and nearly $200,000 in jewelry — including a gold bracelet with the name "Paulie" spelled in diamonds — in a safe hidden in the crawl space of his Itasca home, court records show. A 300-pound union bodyguard who was working with Carparelli, George Brown, began secretly cooperating with the FBI.

In a 2013 recorded conversation between the two men, a transcript of which was submitted by McShain in the presentencing court filings, they discussed how to confront a man who owed them money.

Brown: "What exactly do you want this guy to do if this fat (expletive) doesn't have the money?" Brown asks.Carparelli: "OK, if he doesn't have a check today, we need to ring his bell and ask him when are some funds gonna start being available. ..." Carparelli said.

Brown: "Alright, so he's got the go-ahead to (expletive) blast him? That's what you want?"

Carparelli: "Well, I ... I ... I want, I want a response from him first, I want a response from him first, you know what I mean? You understand what I'm sayin'?"

Brown: "Hold on."

Carparelli: "I'd rather just, I'd rather just go there and get a response from him and then, and then if that doesn't work, then we blast him."

In pleading guilty, Carparelli admitted involvement in plots to use intimidation and violence to collect debts on behalf of two businessmen. He was remanded into federal custody for threatening a government cooperator in August. He then wrote a series of emails and made calls to several friends and associates, including attempts to settle debts and finalize the closing of the deli he operated with the man he became upset with in the emails.

"Hey dude at somepoint we need to have a conversation dont know what your problem is but im not gonna be here forever you cant dodge me BUDDY!!!!! so quit being a FINK and answer my call!!!!!!!!" Carparelli wrote to the man on Aug. 7, under the subject header "yo."

Sentencing is scheduled for Dec. 21.

poconnell@tribpub.com

Twitter @pmocwriter

Copyright © 2015, Chicago Tribune

Reputed mob crew member not hot on firefighter career

written by Sun-Times Staff posted: 12/20/2015, 06:30pm

Reputed Cicero street crew member Paul Carparelli wants a federal judge to give him a break when he is sentenced Monday for extorting money from debtors because he once served as a suburban firefighter.

Federal prosecutors, though, say Carparelli isn’t exactly firefighter-of-the-year material, according to a transcript of a secretly recorded conversation. He wasn’t keen on running into houses on fire for the

few years he worked in west suburban Bloomingdale.

“I said for twenty-eight grand a year, I’ll drive you, and you guys wanna go fight the fire, I’ll go get the donuts,” Carparelli is quoted as saying in a transcript of a phone conversation he had with one of his goons in March 2012. Carparelli, 48, wasn’t high on helping people.“It just wasn’t the job for me, you know. You gotta help them f—— people,” Carparelli said

Nor was he crazy about helping the elderly, who would call in the middle of the night with health problems and disrupt his sleep at the fire station, according to the transcript. “So the fire response is always pickin’ up them old f—in’ f—ers that are croakin’ in the nursing home. You know what I mean?” he asks.

“The lady, oh, I’m havin’ chest pains, I’m havin’ chest pains. She says I’ve been havin’ chest pains since 6:30, 7:00, you know, at night. I looked at her, I said lady, it’s 2:00 in the morning. You wait until 2:00 in the morning and call us, why didn’t you call us at 7:00, you woke everybody up,” Carparelli said, according to the transcript. “She looked at me and got hot,” he adds, laughing.

In May, Carparelli pleaded guilty to his key role in a series of extortion conspiracies around Chicago as well as in Las Vegas, the East Coast and one in Wisconsin that caused the debtor to urinate in his pants and hand over a Ford Mustang because he feared Carparelli’s henchmen.

Carparelli wants probation. A single parent, he says he needs to be out to take care of his teenage son. Federal prosecutors want the judge to sentence him to more than 11 years behind bars.

The feds say he’s a key associate of organized crime figures in Chicago, while his attorney contends Carparelli is nothing more than a big-talking wannabe wise guy.

Contributing: Jon Seidel

Federal prosecutors, though, say Carparelli isn’t exactly firefighter-of-the-year material, according to a transcript of a secretly recorded conversation. He wasn’t keen on running into houses on fire for the

“I said for twenty-eight grand a year, I’ll drive you, and you guys wanna go fight the fire, I’ll go get the donuts,” Carparelli is quoted as saying in a transcript of a phone conversation he had with one of his goons in March 2012. Carparelli, 48, wasn’t high on helping people.“It just wasn’t the job for me, you know. You gotta help them f—— people,” Carparelli said

Nor was he crazy about helping the elderly, who would call in the middle of the night with health problems and disrupt his sleep at the fire station, according to the transcript. “So the fire response is always pickin’ up them old f—in’ f—ers that are croakin’ in the nursing home. You know what I mean?” he asks.

“The lady, oh, I’m havin’ chest pains, I’m havin’ chest pains. She says I’ve been havin’ chest pains since 6:30, 7:00, you know, at night. I looked at her, I said lady, it’s 2:00 in the morning. You wait until 2:00 in the morning and call us, why didn’t you call us at 7:00, you woke everybody up,” Carparelli said, according to the transcript. “She looked at me and got hot,” he adds, laughing.

In May, Carparelli pleaded guilty to his key role in a series of extortion conspiracies around Chicago as well as in Las Vegas, the East Coast and one in Wisconsin that caused the debtor to urinate in his pants and hand over a Ford Mustang because he feared Carparelli’s henchmen.

Carparelli wants probation. A single parent, he says he needs to be out to take care of his teenage son. Federal prosecutors want the judge to sentence him to more than 11 years behind bars.

The feds say he’s a key associate of organized crime figures in Chicago, while his attorney contends Carparelli is nothing more than a big-talking wannabe wise guy.

Contributing: Jon Seidel

Mob associate gets 4 years in prison for plotting to break debtor's legs

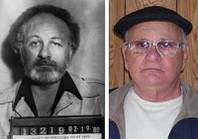

A longtime associate of reputed Outfit bosses Peter and John DiFronzo was convicted Monday of extortion for threatening a deadbeat suburban businessman and then hiring a team of goons to break the victim's legs months later when he still wouldn't pay up hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.

Jason MeisnerContact ReporterChicago Tribune.

Mob associate given four years in prison for plotting to break both legs of car dealer who owed him $250,000

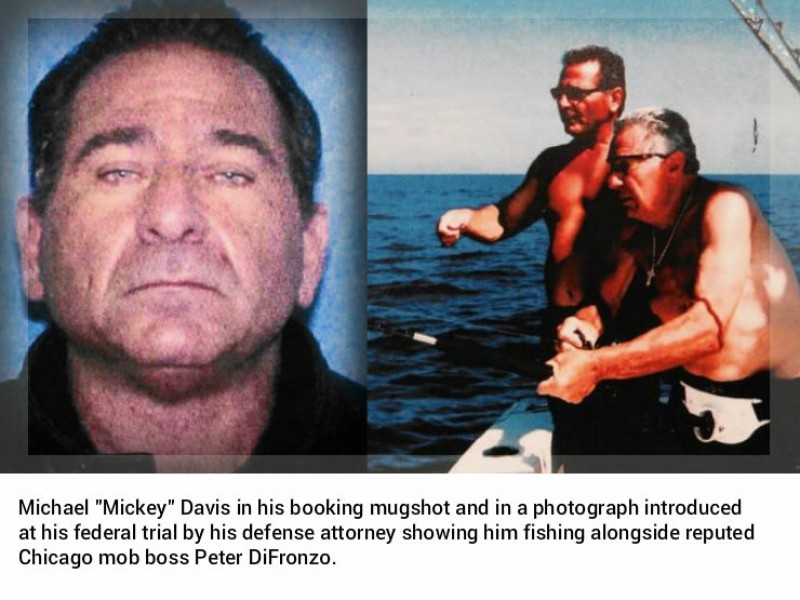

The two mob-connected tough guys were expecting a big payday for breaking the legs of a deadbeat suburban businessman, but like any job it came with its own headaches.

The guy who had ordered the beating, Michael "Mickey" Davis, wasn't just anybody. He was a longtime partner of reputed mob lieutenant Salvatore "Solly D" DeLaurentis and had Outfit connections that purportedly went all the way to the top.

Davis was looking for a crew that would administer a vicious beating to Melrose Park used car dealer R.J. Serpico for failing to pay back a $300,000 loan. He wanted the beating to look like a domestic incident. And he wanted it done in short order, court records show.

"We definitely can't (expletive) around with these guys or we're gonna have a big (expletive) headache," Paul Carparelli, the man entrusted to get the beating done, told his associate in a series of recorded phone calls in July 2013. "The guy already gave the down payment. He's a (expletive) mean mother(expletive). I don't wanna have no problems with him."

Unbeknownst to Carparelli, the beefy union bodyguard he'd enlisted to coordinate the assault, George Brown, had been nabbed months earlier in an unrelated plot and was secretly cooperating with the FBI. In July 2013, agents swooped in to stop the beating before it was carried out.

On Tuesday, Davis was sentenced to four years in prison for ordering the violent assault that seemed ripped from the pages of a low-grade gangster film.

"No one is above the law, and the means used, breaking legs, should only be seen in the movies," U.S. District Judge Samuel Der-Yeghiayan said in handing down the sentence.

Davis, 58, a wealthy landfill owner, showed no emotion as the decision was announced. In the courtroom gallery, several family members wiped tears from their eyes, and Davis' wife, Lisa, doubled over at the waist and stared at the floor.

Davis was convicted in June of two extortion-related counts. Prosecutors had asked Der-Yeghiayan for a sentence of up to six years in prison, saying Serpico still suffers from lingering psychological issues stemming from the ordeal.

Serpico testified at trial that he was afraid he would "end up dead" after Davis paid a visit to Ideal Motors one day in early 2013 and demanded his money back. According to Serpico, Davis asked him in a thinly veiled threat, "How are your wife and kids doing? Are you still living in Park Ridge? Does your wife still own that salon in Schaumburg?"

"These kind of people are — they are ruthless," Serpico testified. "And they're going to do whatever they can to get their money."

Serpico testified at trial that he was well aware of Davis' friendship with reputed Outfit bosses John and Peter DiFronzo and that he often saw Davis and Peter DiFronzo cruising past his Ideal Motors dealership in DiFronzo's black Cadillac Escalade. Serpico said he also had heard that Davis was partnered with DeLaurentis, a feared capo convicted in the 1990s of racketeering conspiracy in connection with a violent gambling crew.

Prosecutors allege that within months of the ominous confrontation at Ideal Motors, Davis, infuriated that Serpico had still failed to pay back the loan, ordered his brutal beating, enlisting the help of the owner of a well-known Italian restaurant in Burr Ridge to find the right guys for the job. The restaurateur went to Carparelli, who in turn hired a team to carry out the beating for $10,000, according to prosecutors. Carparelli pleaded guilty to a separate extortion in May.

Davis' lawyer, Thomas Anthony Durkin, said Davis has known the DiFronzo brothers since childhood and that for years he has maintained a business relationship with them through his landfill in Plainfield, where two DiFronzo-owned construction companies have paid millions of dollars to dump asphalt and other debris.

Durkin even showed jurors a photograph that Davis kept on his office desk of him and a shirtless Peter DiFronzo deep-sea fishing off the coast of Mexico.

In court Tuesday, Durkin painted a picture of Davis as a kind and generous person who overcame a hardscrabble upbringing on Chicago's Northwest Side to become a successful businessman.

"He's not a mobster. There's no evidence of that whatsoever," Durkin said. "Unfortunately, in this town there are people who have grown up with people like that, but it doesn't mean you can't speak to them, it doesn't mean you can't play golf with them."

jmeisner@tribpub.com

Twitter @jmetr22b

The guy who had ordered the beating, Michael "Mickey" Davis, wasn't just anybody. He was a longtime partner of reputed mob lieutenant Salvatore "Solly D" DeLaurentis and had Outfit connections that purportedly went all the way to the top.

"We definitely can't (expletive) around with these guys or we're gonna have a big (expletive) headache," Paul Carparelli, the man entrusted to get the beating done, told his associate in a series of recorded phone calls in July 2013. "The guy already gave the down payment. He's a (expletive) mean mother(expletive). I don't wanna have no problems with him."

Unbeknownst to Carparelli, the beefy union bodyguard he'd enlisted to coordinate the assault, George Brown, had been nabbed months earlier in an unrelated plot and was secretly cooperating with the FBI. In July 2013, agents swooped in to stop the beating before it was carried out.

On Tuesday, Davis was sentenced to four years in prison for ordering the violent assault that seemed ripped from the pages of a low-grade gangster film.

"No one is above the law, and the means used, breaking legs, should only be seen in the movies," U.S. District Judge Samuel Der-Yeghiayan said in handing down the sentence.

Davis, 58, a wealthy landfill owner, showed no emotion as the decision was announced. In the courtroom gallery, several family members wiped tears from their eyes, and Davis' wife, Lisa, doubled over at the waist and stared at the floor.

Davis was convicted in June of two extortion-related counts. Prosecutors had asked Der-Yeghiayan for a sentence of up to six years in prison, saying Serpico still suffers from lingering psychological issues stemming from the ordeal.

Serpico testified at trial that he was afraid he would "end up dead" after Davis paid a visit to Ideal Motors one day in early 2013 and demanded his money back. According to Serpico, Davis asked him in a thinly veiled threat, "How are your wife and kids doing? Are you still living in Park Ridge? Does your wife still own that salon in Schaumburg?"

"These kind of people are — they are ruthless," Serpico testified. "And they're going to do whatever they can to get their money."

Serpico testified at trial that he was well aware of Davis' friendship with reputed Outfit bosses John and Peter DiFronzo and that he often saw Davis and Peter DiFronzo cruising past his Ideal Motors dealership in DiFronzo's black Cadillac Escalade. Serpico said he also had heard that Davis was partnered with DeLaurentis, a feared capo convicted in the 1990s of racketeering conspiracy in connection with a violent gambling crew.

Prosecutors allege that within months of the ominous confrontation at Ideal Motors, Davis, infuriated that Serpico had still failed to pay back the loan, ordered his brutal beating, enlisting the help of the owner of a well-known Italian restaurant in Burr Ridge to find the right guys for the job. The restaurateur went to Carparelli, who in turn hired a team to carry out the beating for $10,000, according to prosecutors. Carparelli pleaded guilty to a separate extortion in May.

Davis' lawyer, Thomas Anthony Durkin, said Davis has known the DiFronzo brothers since childhood and that for years he has maintained a business relationship with them through his landfill in Plainfield, where two DiFronzo-owned construction companies have paid millions of dollars to dump asphalt and other debris.

Durkin even showed jurors a photograph that Davis kept on his office desk of him and a shirtless Peter DiFronzo deep-sea fishing off the coast of Mexico.

In court Tuesday, Durkin painted a picture of Davis as a kind and generous person who overcame a hardscrabble upbringing on Chicago's Northwest Side to become a successful businessman.

"He's not a mobster. There's no evidence of that whatsoever," Durkin said. "Unfortunately, in this town there are people who have grown up with people like that, but it doesn't mean you can't speak to them, it doesn't mean you can't play golf with them."

jmeisner@tribpub.com

Twitter @jmetr22b

Copyright © 2015, Chicago Tribune

Reputed mobster’s sentencing delayed

written by Andy Grimm posted: 12/21/2015, 09:52am

U.S. District Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman reportedly wanted to take more time to consider the large amount of information filed in advance of the sentencing hearing for Paul Carparelli.

There was a wide disparity between the two sides expectations, with Carparelli seeking probation and the feds asking for a sentence of more than 11 years.

Carparelli pleaded guilty in May to his key role in a series of extortion conspiracies around Chicago as well as in Las Vegas, the East Coast and one in Wisconsin that caused the debtor to urinate in his pants and hand over a Ford Mustang because he feared Carparelli’s henchmen.

Carparelli’s request for probation asserted that because he’s a single parent, he needs to be out of prison to take care of his teenage son. Federal prosecutors, in contrast, were asking for a sentence of 135 months — that’s 11 years and 3 months.

The feds captured the reputed Cicero Street Crew member’s colorful way with words on thousands of secret recordings as he bossed around a 300-pound enforcer, ordered up brutal beatings, and concerned himself only with the hierarchy of the Chicago Outfit.

The feds say he’s a key associate of organized crime figures in Chicago, while his attorney contends Carparelli is nothing more than a big-talking wannabe wise guy.

In U.S. District Court filings, Carparelli also asked Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman for a break because he was once a firefighter.

Federal prosecutors, though, say Carparelli isn’t exactly firefighter-of-the-year material, according to a transcript of a secretly recorded conversation.

He wasn’t keen on running into houses on fire for the few years he worked in west suburban Bloomingdale.

“I said for twenty-eight grand a year, I’ll drive you, and you guys wanna go fight the fire, I’ll go get the donuts,” Carparelli is quoted as saying in a transcript of a phone conversation he had with one of his goons in March 2012.

Carparelli, 48, said: “It just wasn’t the job for me, you know. You gotta help them f—— people.”

The extensive conversations recorded by federal prosecutors are laced with profanity and racial epithets, as Carparelli disparages the elderly and African-American people he would be called upon to assist on the job.

In other recordings, Carparelli demanded that the “f—ing thorough beating” of a car salesman in Melrose Park include broken legs. Other times, the feds say he described the beatings more simply: “Guy gets out of his car. Boom, boom, boom. That’s it.” But they said he also once asked the enforcer to “just beat the living p—” out of his ex-wife for $5,000.

Ed Wanderling, Carparelli’s attorney, has called his client a “typical wannabe who watched the Godfather and Sopranos too much.” He called prosecutors’ claims that Carparelli was part of the Cicero Street Crew “ridiculous,” and he pointed to the extensive surveillance of his client.

Prosecutors also say Carparelli has twice this year made threats — once against a government witness, and a second threat by email against a former business partner, made from jail.

The investigation that nabbed Carparelli has already resulted in prison sentences for several of Carparelli’s associates, including five years for Robert McManus, four years for Michael “Mickey” Davis, 46 months for Mark Dziuban and Frank Orlando, and 38 months for Vito Iozzo.

Carparelli, of Itasca, was arrested July 23, 2013, as he drove up to his home with his son in the car, according to the feds. He had cocaine and tested positive for it, and agents found two guns and $175,000 cash in his home.

Carparelli’s request for probation asserted that because he’s a single parent, he needs to be out of prison to take care of his teenage son. Federal prosecutors, in contrast, were asking for a sentence of 135 months — that’s 11 years and 3 months.

The feds captured the reputed Cicero Street Crew member’s colorful way with words on thousands of secret recordings as he bossed around a 300-pound enforcer, ordered up brutal beatings, and concerned himself only with the hierarchy of the Chicago Outfit.

The feds say he’s a key associate of organized crime figures in Chicago, while his attorney contends Carparelli is nothing more than a big-talking wannabe wise guy.

In U.S. District Court filings, Carparelli also asked Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman for a break because he was once a firefighter.

Federal prosecutors, though, say Carparelli isn’t exactly firefighter-of-the-year material, according to a transcript of a secretly recorded conversation.

He wasn’t keen on running into houses on fire for the few years he worked in west suburban Bloomingdale.

“I said for twenty-eight grand a year, I’ll drive you, and you guys wanna go fight the fire, I’ll go get the donuts,” Carparelli is quoted as saying in a transcript of a phone conversation he had with one of his goons in March 2012.

Carparelli, 48, said: “It just wasn’t the job for me, you know. You gotta help them f—— people.”

The extensive conversations recorded by federal prosecutors are laced with profanity and racial epithets, as Carparelli disparages the elderly and African-American people he would be called upon to assist on the job.

In other recordings, Carparelli demanded that the “f—ing thorough beating” of a car salesman in Melrose Park include broken legs. Other times, the feds say he described the beatings more simply: “Guy gets out of his car. Boom, boom, boom. That’s it.” But they said he also once asked the enforcer to “just beat the living p—” out of his ex-wife for $5,000.

Ed Wanderling, Carparelli’s attorney, has called his client a “typical wannabe who watched the Godfather and Sopranos too much.” He called prosecutors’ claims that Carparelli was part of the Cicero Street Crew “ridiculous,” and he pointed to the extensive surveillance of his client.

Prosecutors also say Carparelli has twice this year made threats — once against a government witness, and a second threat by email against a former business partner, made from jail.

The investigation that nabbed Carparelli has already resulted in prison sentences for several of Carparelli’s associates, including five years for Robert McManus, four years for Michael “Mickey” Davis, 46 months for Mark Dziuban and Frank Orlando, and 38 months for Vito Iozzo.

Carparelli, of Itasca, was arrested July 23, 2013, as he drove up to his home with his son in the car, according to the feds. He had cocaine and tested positive for it, and agents found two guns and $175,000 cash in his home.

Pal of Outfit boss gets 4 years for extortion

Reputed mob associate Mickey Davis, in background, leaves federal court in Chicago Tuesday. |Brian Jackson/Sun-Times Media

Reputed mob associate Mickey Davis, in background, leaves federal court in Chicago Tuesday. |Brian Jackson/Sun-Times Media

It was a scene straight out of a mobster movie.

Michael “Mickey” Davis stepped into the Melrose Park used-car dealer’s office, shut the door and took a seat. He dropped a sheet of gambling debts on R.J. Serpico’s desk and growled, “this wasn’t the f—ing agreement.” Then he leaned back in his chair, and he asked two simple questions: “How are your wife and kids? Do you still live in Park Ridge?”

That moment in January 2013 could have come straight from Hollywood, a federal prosecutor wrote this month. But “when you grow up in Melrose Park, the mob is not fiction or something that you only see in movies,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Heather McShain said. Six months after that confrontation, she said Davis ordered Serpico’s “f—ing thorough beating.”

But it never happened. The “300-pound muscle guy” hired to break Serpico’s legs turned out to be a government informant. And Tuesday, U.S. District Judge Samuel Der-Yeghiayan sentenced Davis to four years in prison for extortion and attempted extortion.

“No one is above the law, and the means used, breaking legs, should only be seen in the movies,” Der-Yeghiayan said.

Davis’ attorney, Thomas Anthony Durkin, asked the judge for mercy Tuesday. He said Davis has led an impressive life considering his hardscrabble background

He also said Davis has had mini-strokes and is in need of “serious medical treatment.”

Davis declined to speak at length to the judge before his sentencing, saying only, “I think Mr. Durkin said it all.” Outside the courtroom, Davis had no comment either.

Davis, 58, grew up in a “rough and tumble” Logan Square of decades past that “would be more familiar to Studs Lonigan and Studs Terkel, than today’s trendy coffee shops and fine dining restaurants,” his lawyers wrote.

The feds say Davis became “wealthy, successful, and supported by his family and friends.” But he associated with known members of the Chicago Outfit and even vacationed with Pete DiFronzo, a man described in trial testimony as the Outfit’s “street boss.”

Davis loaned $300,000 to R.J. Serpico and his father, Joe, in Spring 2012 to start Ideal Motors, a used-car dealership in Melrose Park. Davis expected his money back within three years, as well as $300 for every car sold. But the dealership was already in financial trouble within a few months, and Joe Serpico “had a serious gambling problem,” prosecutors said.

When the dealership stopped holding up its end of the bargain, Davis confronted R.J. Serpico in his office, throwing around a sheet of Joe Serpico’s gambling debts, as well as veiled threats like, “How old are your kids? Does your wife still have that salon in Schaumburg?”

When Davis was finished, prosecutors said he stood up, leaned over the desk, stared at R.J. Serpico, and left.

Davis later convinced R.J. Serpico to fire his father. Serpico told a jury that he feared Davis. He said he saw Davis driving around with DiFronzo and thought to himself, “what did I get myself into?” He agreed to sign over the title of a Chevrolet Chevelle to Davis, who sold it for $30,000, records show. He also paid Davis an additional $30,900.

But Serpico walked off the lot of Ideal Motors in May 2013, never to return, according to the feds. Davis allegedly arranged for a friend to take over operations and had the vehicles towed to a lot owned by DiFronzo.

In June or early July 2013, the feds say Davis arranged for Serpico’s “break-both-legs beating” by contacting Gigi Rovito, who recruited Paul Carparelli, who reached out to George Brown. Carparelli told Brown the person who ordered the beating was “Mickey” who was “Solly D’s partner” — an apparent reference to Chicago Outfit member Salvatore DeLaurentis.

Brown initially mistook R.J. Serpico for the son of Melrose Park Mayor Ronald Serpico, records show. R.J. Serpico is actually the mayor’s nephew.

The feds say Davis dropped off a $5,000 down payment for the beating at Rovito’s Capri Ristorante on July 11, 2013. But Brown turned out to be a federal informant. Carparelli was arrested July 23, 2013, and now faces sentencing in a separate extortion case Dec. 21. Davis was indicted in March 2014.

Meanwhile, the feds say they used cell phone data to track Davis’ movements the day he dropped off the $5,000.

They said he had come that day from the Itasca Country Club, where he played a round of golf with, “or immediately next to,” DiFronzo.

Michael “Mickey” Davis stepped into the Melrose Park used-car dealer’s office, shut the door and took a seat. He dropped a sheet of gambling debts on R.J. Serpico’s desk and growled, “this wasn’t the f—ing agreement.” Then he leaned back in his chair, and he asked two simple questions: “How are your wife and kids? Do you still live in Park Ridge?”

Mob associate Mickey Davis appears to try to hide behind a water bottle as he leaves federal court in Chicago Tuesday. | Brian Jackson/Sun-Times Media

He also said Davis has had mini-strokes and is in need of “serious medical treatment.”

Davis declined to speak at length to the judge before his sentencing, saying only, “I think Mr. Durkin said it all.” Outside the courtroom, Davis had no comment either.

Davis, 58, grew up in a “rough and tumble” Logan Square of decades past that “would be more familiar to Studs Lonigan and Studs Terkel, than today’s trendy coffee shops and fine dining restaurants,” his lawyers wrote.

The feds say Davis became “wealthy, successful, and supported by his family and friends.” But he associated with known members of the Chicago Outfit and even vacationed with Pete DiFronzo, a man described in trial testimony as the Outfit’s “street boss.”

Davis loaned $300,000 to R.J. Serpico and his father, Joe, in Spring 2012 to start Ideal Motors, a used-car dealership in Melrose Park. Davis expected his money back within three years, as well as $300 for every car sold. But the dealership was already in financial trouble within a few months, and Joe Serpico “had a serious gambling problem,” prosecutors said.

When the dealership stopped holding up its end of the bargain, Davis confronted R.J. Serpico in his office, throwing around a sheet of Joe Serpico’s gambling debts, as well as veiled threats like, “How old are your kids? Does your wife still have that salon in Schaumburg?”

When Davis was finished, prosecutors said he stood up, leaned over the desk, stared at R.J. Serpico, and left.

Davis later convinced R.J. Serpico to fire his father. Serpico told a jury that he feared Davis. He said he saw Davis driving around with DiFronzo and thought to himself, “what did I get myself into?” He agreed to sign over the title of a Chevrolet Chevelle to Davis, who sold it for $30,000, records show. He also paid Davis an additional $30,900.

But Serpico walked off the lot of Ideal Motors in May 2013, never to return, according to the feds. Davis allegedly arranged for a friend to take over operations and had the vehicles towed to a lot owned by DiFronzo.

In June or early July 2013, the feds say Davis arranged for Serpico’s “break-both-legs beating” by contacting Gigi Rovito, who recruited Paul Carparelli, who reached out to George Brown. Carparelli told Brown the person who ordered the beating was “Mickey” who was “Solly D’s partner” — an apparent reference to Chicago Outfit member Salvatore DeLaurentis.

Brown initially mistook R.J. Serpico for the son of Melrose Park Mayor Ronald Serpico, records show. R.J. Serpico is actually the mayor’s nephew.

The feds say Davis dropped off a $5,000 down payment for the beating at Rovito’s Capri Ristorante on July 11, 2013. But Brown turned out to be a federal informant. Carparelli was arrested July 23, 2013, and now faces sentencing in a separate extortion case Dec. 21. Davis was indicted in March 2014.

Meanwhile, the feds say they used cell phone data to track Davis’ movements the day he dropped off the $5,000.

They said he had come that day from the Itasca Country Club, where he played a round of golf with, “or immediately next to,” DiFronzo.

Quartet of books marks Frank Sinatra centenary

A hundred years ago this Dec. 12, under the sign of Sagittarius, in the shadow of World War I and in the gritty embrace of Hoboken, N.J., Natalie Catherine Garavente Sinatra — "Dolly" — gave birth to a boy named Francis Albert. What happened next, in the fast-forwarded meaning of that word, has written itself as much as it has been written via a Babel-like tower of books, articles, liner notes, gossip columns, lecture notes, film scripts, websites and fan scribblings.

Now, on the cusp of this milestone moment in Sinatriana, long after RPM stopped meaning anything, we are being treated to yet more books about his time on Earth, the place he occupies in American culture and the role he plays in our lives.

The question is, particularly in the wake of HBO's two-part, four-hour documentary, "Sinatra: All or Nothing at All," are you ready to dive back into the subject?

Now, on the cusp of this milestone moment in Sinatriana, long after RPM stopped meaning anything, we are being treated to yet more books about his time on Earth, the place he occupies in American culture and the role he plays in our lives.

For hard-wired Frankophiles, of course, there is no such thing as too much, meaning that "Sinatra: The Chairman," James Kaplan's nearly 1,000-page sequel to his 800-page doorstop of 2010, "Frank: The Voice," couldn't have come a moment too soon.

For fans with less time on their hands, there is John Brady's "Frank & Ava: In Love and War," a polished recap of Sinatra's thorny, epic romance with the goddess-like Ms. Gardner that is padded with unrelated material but goes down smoothly.

David Lehman's browser-friendly "Sinatra's Century" offers "One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World" — "Godfather" references, Elvis Costello's analysis of Sinatra's vocals, the anagrams in Sinatra's name, a list of Italian singers and their real names.

"The Chairman," clearly the main event here, picks up the story in 1954, when a best supporting actor Oscar for "From Here to Eternity" fueled Sinatra's remarkable comeback from a painful downturn in his career — and his downward spiral after Ava Gardner's arrival in Nevada to spend the required time in residence for her divorce suit against him.

With Sinatra's return to success came a full flowering of his extremes. Here was a man who was capable of the most loutish, temperamental behavior and the sweetest, most generous gestures; the truest friend anyone could have (ask Sammy Davis Jr.) and the world's worst grudge-holder; a man committed to important social causes even while drawn to the Mafia.

During these tumultuous years in his life, Sinatra reached incomparable heights as a singer and interpreter of song. In due course, he invented the concept album with the brooding masterpiece, "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning" (1955). He perfected his hard-swinging, ring-a-dingy sound and, under the influence of Billie Holiday, re-equipped his style (and redefined the popular vocal) with deep adult emotion.

We learn from Kaplan that Sinatra, an only child who "lived with loneliness" and torment, was constitutionally unable to stay in one place or be by himself. To combat the chronic suffering that dogged him his entire life, he had to keep in motion, preferably surrounded by friends. The original Rat Pack, including Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall (with whom he became romantically entangled while Bogie lay dying) was the ultimate in great company — though the Dean Martin version was no slouch when it came to carousing.

Sinatra may have celebrated matrimony with his 1955 hit, "Love and Marriage" (written for a TV production of "Our Town"). But wedlock never prevented him from playing the field. There was no beauty the powerful and charismatic Sinatra could not get into bed (he made a list of the ones to go after), including Marilyn Monroe.

Following her divorce from Joe DiMaggio, Monroe was going through a difficult period — too difficult for Sinatra to cope with on his pleasure yacht. "I was ready to throw her right off that f— boat," he is quoted as telling an associate. Citing opposing sources, Kaplan is inconclusive about which party was more smitten, but he is happy to write, per Sinatra's longtime valet, that the singer was "disgusted by Marilyn's slovenliness and disdainful of her intellect." Kaplan also can't resist a frowning assessment of Monroe's physical state, based on a photograph of her with Sinatra, describing her as "overweight — her chin is double — and … distinctly less than glamorous."

How much you'll want to read about Sinatra's romantic misadventures with Ava Gardner, detailed in three of the books (Lehman has them on a drunken joy ride in Palm Springs shooting out streetlights and store windows with .38s) will depend on your stamina. Here was a matchup of two demanding, extravagantly self-centered souls who helplessly clung to the idea of their romance long after their disaster of a marriage ended.

Would Sinatra have poured such depths of feeling into songs such as "I'm A Fool to Want You" had he not suffered over the loss of his green-eyed goddess? Kaplan is not alone in saying no. The deepening of Sinatra's voice physically, on the other hand, was a consequence of his drinking and sleepless nights. There were times his instrument was so damaged he was unable to use it.

Like its subject, "The Chairman" has to keep moving. Its subjects range from Elvis Presley, who with his higher popularity rating would have gotten under Sinatra's skin even if he didn't play that hated rock 'n' roll, to Mia Farrow, whose May-December marriage to Sinatra inspires some of the book's most insightful writing, to the casino manager who socked Sinatra in the face.

Sinatra, whose prodigious sex drive gave him and John F. Kennedy something in common — "Sinatra's Century" contains Rat Packer and Kennedy in-law Peter Lawford's admission that "he was Frank's pimp and Frank was Jack's" — campaigned hard for his friend and produced his inaugural celebration.

Sinatra had arranged to have JFK stay with him during a trip to California early in his presidency. But tainted by his association with Sam Giancana and the Chicago mob — which he allegedly enlisted to muscle votes for Kennedy in key states — Sinatra got stood up. Kennedy stayed instead with Bing Crosby — a hard-line Republican. (Helplessly drawn to power, Sinatra later palled around with Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew.)

In stringing all these chapters together, Kaplan comes across as part tour guide and part bricklayer. But though he contradicts himself on Sinatra's capacity for joy, and all but ignores the pretentious pile-up that was Sinatra's three-album opus, "Trilogy: Past Present Future," he offers sound evaluations of key recordings and solid reporting on celebrated sessions. Sinatra was at constant war with his record labels. To punish Capitol for not rewarding him enough, he recorded the songs for "Sinatra's Swingin' Session!!!" at twice the normal tempo (it was a hit, nonetheless). He also fell out with most of his arrangers. In a lovely gesture to a dying man, he brought back Axel Stordahl, one of his earliest arrangers, for "Point of No Return," his Capitol swan song. But in the studio, he treated him shabbily.

One can only hope that when Sinatra began forgetting lyrics he had sung thousands of times, the people around him were kinder. He may have been a cad, but he was our cad — a transcending soul who has continued lifting our lives on a daily basis.

One can only hope that when Sinatra began forgetting lyrics he had sung thousands of times, the people around him were kinder. He may have been a cad, but he was our cad — a transcending soul who has continued lifting our lives on a daily basis.

Oscar Goodman, ex-FBI agent tangle over real-life 'Casino' story

By Jane Ann Morrison

Las Vegas Review-Journal

Las Vegas Review-Journal

Although I have never been a perp, I participated on a famous perp walk in 1983 and have the black-and-white photo to prove it.

The perp was later-to-be-murdered mobster Anthony Spilotro. The serious-looking FBI agent walking him by the press was Marc Kaspar.

The journalists waiting to ask questions that wouldn't be answered were George Knapp and the R-J's federal court reporter at the time. That would be me. The one with the Afro.

During a panel Saturday, Kaspar told the behind-the-scenes story of that perp walk outside the Foley Federal Building.

Spilotro had been indicted on racketeering by a federal grand jury, and Kaspar went to arrest him. The two men had known each other for years because Kaspar has been on the FBI's Las Vegas organized crime squad since coming to Las Vegas in 1977, and the squad's No. 1 target was the Chicago mob's enforcer.

You would think they would be bitter enemies. Not so. When Spilotro was arrested, Kaspar didn't even use his handcuffs. Until they got close to the federal building and Kaspar said, "Tony, I've got to put handcuffs on you."

Spilotro offered his hands up, he was cuffed, and they did the perp walk. Kaspar knew what he had to do, so did Spilotro; it was all very professional.

Kaspar has donated those cuffs to the Mob Museum, which hosted the Saturday panel discussion of what was real and what was fiction in the 1995 movie "Casino."

Kaspar was speaking out publicly for the first time about his experiences as the case agent in the Spilotro investigation.

Oscar Goodman gave his views from the perspective of the attorney representing Spilotro and his chum Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal.

Former Gaming Control Board member Jeff Silver spoke about his role chasing the mob as a state regulator.

Former FBI agent Deborah Richard told her experience in two previous columns, and retired television reporter and anchor Gwen Castaldi told of the challenges facing journalists covering the mob in the 1970s and 1980s.

As Castaldi said, without cellphones and the Internet, it wasn't easy, especially because news about the mob in Las Vegas was frequently connected to news about the mob in Kansas City, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Detroit and Chicago.

Kaspar told about a 1981 search where the subject — in this case Stardust employee Phil Ponto — had been tipped. The agents searched his apartment looking for marked money that had been skimmed from the Stardust.

The safe was opened, and inside was nothing but Ponto's Social Security check.

It was Ponto's way of flipping off the FBI, much like the simultaneous search that resulted in agents coming up with cookies and a bottle of wine in a car trunk.

While there were plenty of laughs Saturday, there were serious moments. Kaspar said he tried to be diplomatic, but he pushed back against Goodman's statements he believed were not true.

Goodman said things such as Spilotro didn't curse, he and Geri Rosenthal didn't have an affair, Rosenthal was not an FBI informant, and federal Judge Harry Claiborne had not leaked FBI wiretap information to the mob.

Goodman, who went on to become mayor of Las Vegas for 12 years, went on a tirade against former FBI agent Gary Magnesen, who had written in "Straw Men" that he believed the late Claiborne had leaked information from FBI search warrant affidavits so mobsters knew in advance about the searches, which resulted in cookies and a Social Security check.

"Harry Claiborne lived with this accusation until he took his own life," Goodman said angrily.

Except Magnesen's book was published in 2010 and Claiborne committed suicide in 2004. The timing is off.

Kaspar said he believes Claiborne was the leak. "He was the one who signed the wiretap order on the Stardust," the retired agent said. "When I heard that, I told the case agent we'd find nothing but cabbage," he said, referring to the 1981 Ponto search.

Magnesen now believes, as I wrote in last Thursday's column, that mob associate Rosenthal was a double agent and tipped mobsters off to upcoming searches. Magnesen said Rosenthal became an FBI informant around the time he wanted to get a gaming license, an effort that began in 1975. "He wanted the FBI to help him with his gaming license — which we didn't do."

In a tirade, Goodman denied Rosenthal was an informant. "It's poppycock."

Of course, would Rosenthal have admitted it to his attorney?

I confirmed it back in 2008 with three sources. Magnesen said it on the record, and Kaspar said, "I have reason to believe he was." Richard also said he was an informant based on what she had been told. But Goodman doesn't believe it.

Goodman asked if Spilotro was such a bad guy, killing more than 20 peoples, why wasn't he convicted?

"He was never convicted because he got rid of all the evidence," Kaspar said, referring to witnesses who died or disappeared. "I always said we would never convict Tony, that he'd be taken care of by his own people."

Spilotro and his brother Michael were killed, then buried, in an Indiana field in 1986.

"I'm not sure anybody in law enforcement wanted to solve his murder," Goodman said bitterly. He complained no one from law enforcement asked if he had any idea who killed Spilotro.

"You wouldn't tell anyway," Kaspar responded.

Kaspar and Goodman took opposite views on the 1982 bombing of Rosenthal's car. Kaspar believes it was ordered by Spilotro. Goodman made the comment that different families had different styles, and the Kansas City mob leaned toward car bombings. That was identical to Magnesen's opinion, who contends the bombing was ordered by Kansas City mob boss Nick Civella, another of Goodman's clients.

Goodman said the movie captured Rosenthal "but took a lot of license as far as Tony is concerned."

He said Spilotro didn't curse as Joe Pesci did in the movie and was very polite.

Richard, who surveilled the mobster, said Spilotro probably treated his defense attorney "differently than the people he extorted."

Kaspar said the wiretaps showed that Spilotro did curse, and surveillance photos he took himself showed Spilotro and Geri Rosenthal meeting. Their affair was a major storyline in Nick Pileggi's book based on Rosenthal's recollections.

To give Goodman the last word: "Those folks would still be running casinos if they weren't so greedy."

Seems like he's in a position to know, even if his memory can be faulty.

Jane Ann Morrison's column runs Thursdays. Leave messages for her at 702-383-0275 or email jmorrison@reviewjournal.com. Find her on Twitter: @janeannmorrison

The perp was later-to-be-murdered mobster Anthony Spilotro. The serious-looking FBI agent walking him by the press was Marc Kaspar.

The journalists waiting to ask questions that wouldn't be answered were George Knapp and the R-J's federal court reporter at the time. That would be me. The one with the Afro.

During a panel Saturday, Kaspar told the behind-the-scenes story of that perp walk outside the Foley Federal Building.

Spilotro had been indicted on racketeering by a federal grand jury, and Kaspar went to arrest him. The two men had known each other for years because Kaspar has been on the FBI's Las Vegas organized crime squad since coming to Las Vegas in 1977, and the squad's No. 1 target was the Chicago mob's enforcer.

You would think they would be bitter enemies. Not so. When Spilotro was arrested, Kaspar didn't even use his handcuffs. Until they got close to the federal building and Kaspar said, "Tony, I've got to put handcuffs on you."

Spilotro offered his hands up, he was cuffed, and they did the perp walk. Kaspar knew what he had to do, so did Spilotro; it was all very professional.

Kaspar has donated those cuffs to the Mob Museum, which hosted the Saturday panel discussion of what was real and what was fiction in the 1995 movie "Casino."

Kaspar was speaking out publicly for the first time about his experiences as the case agent in the Spilotro investigation.

Oscar Goodman gave his views from the perspective of the attorney representing Spilotro and his chum Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal.

Former Gaming Control Board member Jeff Silver spoke about his role chasing the mob as a state regulator.

Former FBI agent Deborah Richard told her experience in two previous columns, and retired television reporter and anchor Gwen Castaldi told of the challenges facing journalists covering the mob in the 1970s and 1980s.

As Castaldi said, without cellphones and the Internet, it wasn't easy, especially because news about the mob in Las Vegas was frequently connected to news about the mob in Kansas City, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Detroit and Chicago.

Kaspar told about a 1981 search where the subject — in this case Stardust employee Phil Ponto — had been tipped. The agents searched his apartment looking for marked money that had been skimmed from the Stardust.